At the end of 2019, following the phase one trade deal between the United States and China, markets continued their near decade long ascendancy with renewed enthusiasm.

The rally rapidly began to lose momentum around February 21 when it became clear that the coronavirus known as COVID-19 was not going to be contained within China and had begun to spread throughout the world. Within days the market began to slide before plummeting as images of hospitals in Italy bursting at the seams, overwhelmed by the sheer scale and magnitude of the disease began to fill the newsfeeds. When it became clear that the unprecedented scale and magnitude of this virus was going to close borders and disrupt businesses around the world for an unknown duration, fear and panic took over and a meltdown ensued as global markets registered some of their heaviest daily falls in history.

At times of extreme fear and uncertainty, investors often lose sight of how shares are fundamentally valued and instead extrapolate worst case scenarios over multi-year time frames without any rational thought. At such times it can be helpful to have at least a basic understanding of the mechanics of share valuations to improve decision making.

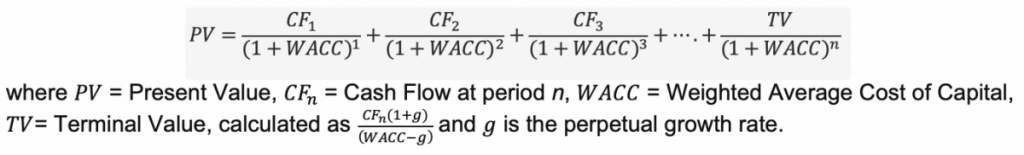

Share valuations are simply the sum of the present value of future cashflows. Mathematically, this can be represented as follows:

While the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 are undoubtedly unprecedented (except for the Spanish flu), there have already been numerous reports of scientific breakthroughs that point to a moderate to high probability of having a commercially available vaccine within 12 to 18 months. Using this logic, we can start to stress test the impact on company valuations.

Example

Based on consensus earnings expectations as at 10 March 2020, the formula derives a fair value for a Big 4 Bank of $25.77. We know it takes time for analysts to revise their earnings expectations in light of any change in circumstances and so the current expectations inevitably will be revised lower in coming months. Nevertheless, even if we assume this bank’s earnings plummet on bad debts in FY20 and FY21, and the bank records no earnings whatsoever over those two years, before rebounding in FY22, the formula derives a fair value of $22.66, which is still well above the actual market value of $15.98 (as at 16 March 2020). Further, in two years’ time, when these bad years are no longer included in the valuation, fair value moves back towards $27 (all other things being equal).

| Big 4 banks | Consensus expectations1 | Stress tested |

| FY20 EPS[1] (f) | $1.65 | $ – |

| FY21 EPS (f) | $1.85 | $ – |

| FY22 EPS (e) | $1.85 | $1.85 |

| Terminal growth rate: | 1.00% | $1.00 |

| Discount Factor – WACC: | 8% | 8% |

| Intrinsic Valuation: | $25.77 | $22.66 |

| Market value 16 March 2020: | $15.98 | $15.98 |

| Potential Under-valuation: | 61% | 42% |

Conclusion

It is important to understand that companies are valued over 20+ year time horizons, not over 6-18 months. During times of fear and panic, an understanding of basic valuation principles can help you make more rational decisions. Equally, it is also important to understand that share valuations are only as good as the assumptions on which they are based. A company that may screen cheap on valuation may ultimately disappoint if the underlying earnings assumptions prove too optimistic. This may be for any number of reasons including because the depth and duration of the recession are worse than expected, the company is poorly managed, costs escalate outside its control, or structural changes reduce its competitive advantages over time. Further, companies with highly cyclical cashflows and stretched balance sheets lumbered with too much debt are highly vulnerable during periods of high economic uncertainty and are more susceptible to failure. These are the value traps that should be avoided no matter how cheap they might appear.