On 9 May, Treasurer Jim Chalmers handed down the FY23-24 Federal Budget. Key areas of focus included:

| Theme | Initiatives |

|---|---|

| Cost of Living relief | Targeted assistance for lower income households and smaller businesses including energy cost subsidies ($1.5b) to lower power bills as well as increased payments for those reliant on government support programs such as Jobseeker ($4.9b) or Commonwealth Rent Assistance ($2.7b) |

| Climate Change | Some direct spending initiatives e.g. $2bn towards starting a green hydrogen industry and a much larger $10bn for upgrading energy infrastructure (the Capacity Investment Scheme) |

This marked the second chance for the Treasurer to make his mark following on from last year’s October update. As it was then, so it was now, a Budget that threaded the line between wanting to appear “fiscally responsible” while also addressing the public outcry on cost-of-living issues in what is a still-elevated inflation and interest rate environment. As it was then, so it was now, a Budget that threaded the line between wanting to appear “fiscally responsible” while also addressing the public outcry on cost-of-living issues in what is a still-elevated inflation and interest rate environment.

Budget financial position

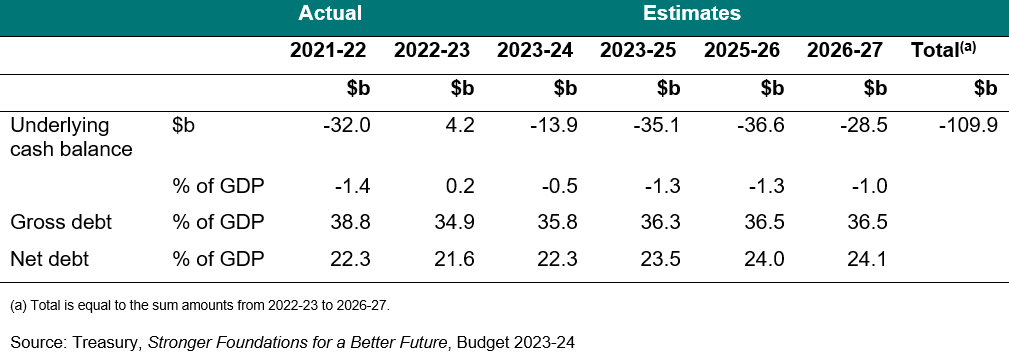

In terms of the underlying budget position the important part is to focus on the underlying cash balance (the “look-through” surplus or deficit) relative to GDP (a proxy for total economic activity and our collective ability to repay). This is now expected to be a slight surplus for FY23 before returning to deficit over subsequent years to a peak of 1.3% in FY26 according to Treasury forecasts. The Budget has benefitted from elevated commodity prices for another year due to pandemic-related production disruptions as well as the war in Ukraine.

If prices remain in line with market forecasts which see iron ore ending 2024 at $US98.75/t[1] versus the Budget Forecast for $US60/t for example, we could see a reasonable prospect of a narrower deficit (or even surplus) again next year as noted by other commentators[2]. The natural rebuttal though would be to note the weaker economic backdrop which is expected to see higher unemployment. That usually translates into weaker spending and wage growth which see government deficits widen due to both paying higher unemployment benefits and collecting less income tax. The lack of clear measures to curtail welfare and healthcare spending e.g. strong growth expected for the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) would also weigh against the potential surplus argument.

Overall, this Budget is seeing the government continue to take a more background stance in the immediate term compared to the sizeable interventions during the pandemic. While there has been some spending towards its longer-term policy initiatives e.g. climate change and the environment these are not of a sufficiently large scale to either impair or bolster public finances. The longer-term question of some observers about sustainability in social welfare programs remains a live issue with the NDIS featuring as one area that may face reductions in the years ahead given the pace of spending growth since its inception.

Economic Outlook

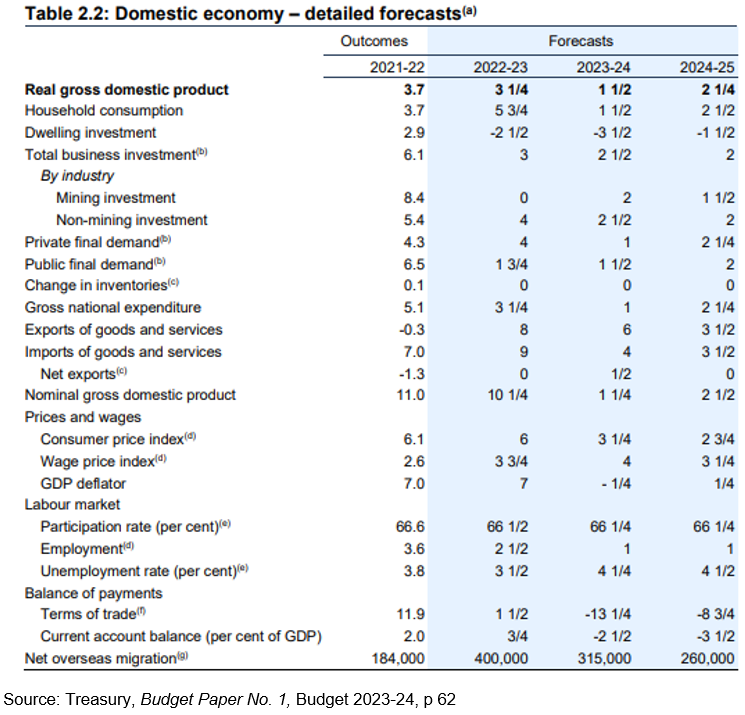

Treasury forecasts continued to suggest some inconsistencies that are difficult to square. The forecast growth economic growth rate of 3.25% for FY23 is looking optimistic versus the RBA (1.7%[3]) or market consensus (1.7%[4]). Admittedly the forecasts are more aligned in subsequent years and paint a tougher backdrop of weaker spending and rising unemployment. Given global growth is also expected to be weak over the next two years, the Budget deficits highlighted above may be wider than expected.

Economic implications

The expectation of government deficits in the above table would, on balance, be counteracting the RBA position where the threat of inflation has seen a rapid pace of interest rate hikes. All else being equal, deficits suggest the government is injecting more into the economy than it is withdrawing via taxation which should be supportive of higher growth (and inflation). The actual scale of the relief packages in this Budget appear relatively modest particularly when put into context. For example, the increase in income support payments of $4.9b over 5 years pales in comparison to the shock households have faced from higher interest rates. Looking at the latest GDP figures they show households paid $9.1b more in mortgage interest for the Dec-22 quarter alone compared to the Dec-21 quarter[5]. Assistance packages of $1b-$1.3b p.a.[6] are not going to materially shift household spending in the aggregate. While it may be slightly expansionary and support some additional household spending on the margins, we see this as an issue on the margins and unlikely to outweigh the impact of existing RBA policy. In addition, the form of relief will take the form of direct subsidies in a number of cases e.g. childcare and utilities that will increase disposable income by lowering these costs. Whether households will automatically spend these gains in aggregate is uncertain given prevailing weak levels of consumer sentiment with the Westpac-MI Consumer Sentiment Index continuing to track at depressed levels last seen at the start of the coronavirus pandemic and prior to that, the global financial crisis[7].

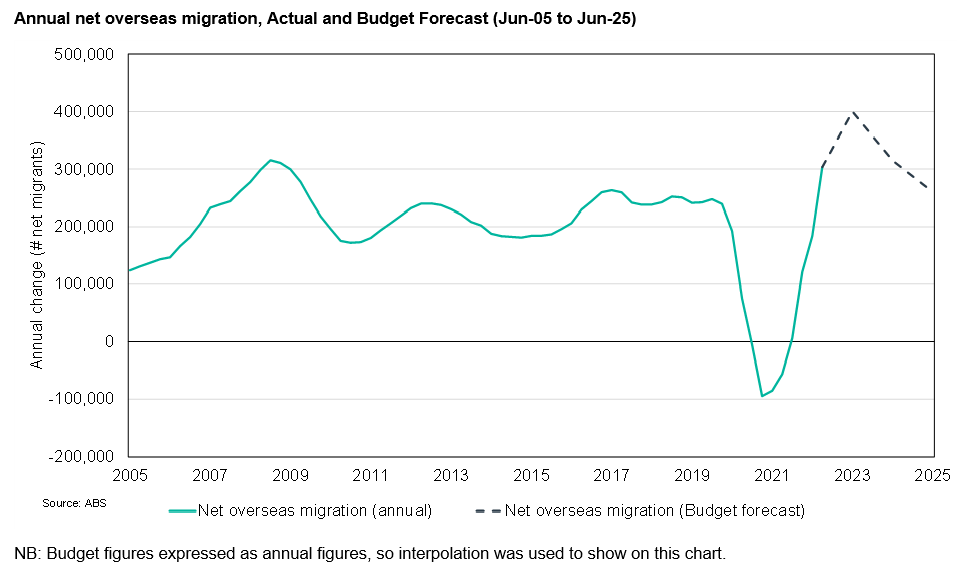

Migration running at elevated levels even more so than the October forecasts may have several implications:

- Boost aggregate economic growth as more people → more demand for goods and services → more spending and higher growth

- Act as a drag on wage growth as more potential workers → boosts labour supply → constrains wages as more potential candidates for businesses to choose from.

- Lead to a disconnect between aggregate and per-capita growth depending on the economic contribution of new migrants

Overall, the Budget should be viewed as mildly opposing the RBA position but with insufficient magnitude to exert a material impact. The lingering questions of structural reform of spending on the NDIS remains a live issue and one that the government is aware of with this Budget flagging sustainability of the scheme as a key concern[8].

Investment implications

The Budget had limited investment implications. Potential beneficiaries are highlighted below but few will see a direct, clearcut benefit immediately. Instead, Budget policies are supportive of longer-term tailwinds adding to demand in our view:

| Policy | Potential beneficiaries[1] |

|---|---|

| Cost of living relief |

|

| Migration |

|

| Real Estate |

|

| Climate change policy |

|

Conclusion

Overall, this Budget looked to address household concerns over the rising cost-of-living to a point. It was not overly ambitious in our assessment. Some of the measures such a lower energy costs and increased government assistance on rents and childcare will help on the margin and arguably be seen as slightly stimulative. Lingering issues of spending sustainability in the NDIS remain deferred into the future.

Finally, it also reflects the limits of government spending, while a powerful tool it cannot “magic from thin air” new housing supply with the pressures there likely to persist in the near term particularly given still ambitious migration forecasts. Unlike other observers we do not see the new spending measures as significant enough to materially sway the RBA as their impact should be modest and outweighed by the broader economic context and the shock posed by a higher interest rate environment.